08 A Little Lagoon

Clay County

Early in the evening, after a pleasant day’s voyage, I made a convenient and safe harbour, in a little lagoon…

William Bartram’s first visit to Clay County occurred on November 21, 1765, when he crossed the St. Johns River in a canoe with his father while attending the Indian Congress at Fort Picolata. The exact location of their landing is unknown, but given William’s tendency to revisit sites he had visited with his father on his previous trip, it is quite possible they were the same.

What we do know is that it was across the River from Fort Picolata, and it was not the ferry landing because they didn’t mention the relic site of Fort de Pupo, which they visited on February 2, 1766.

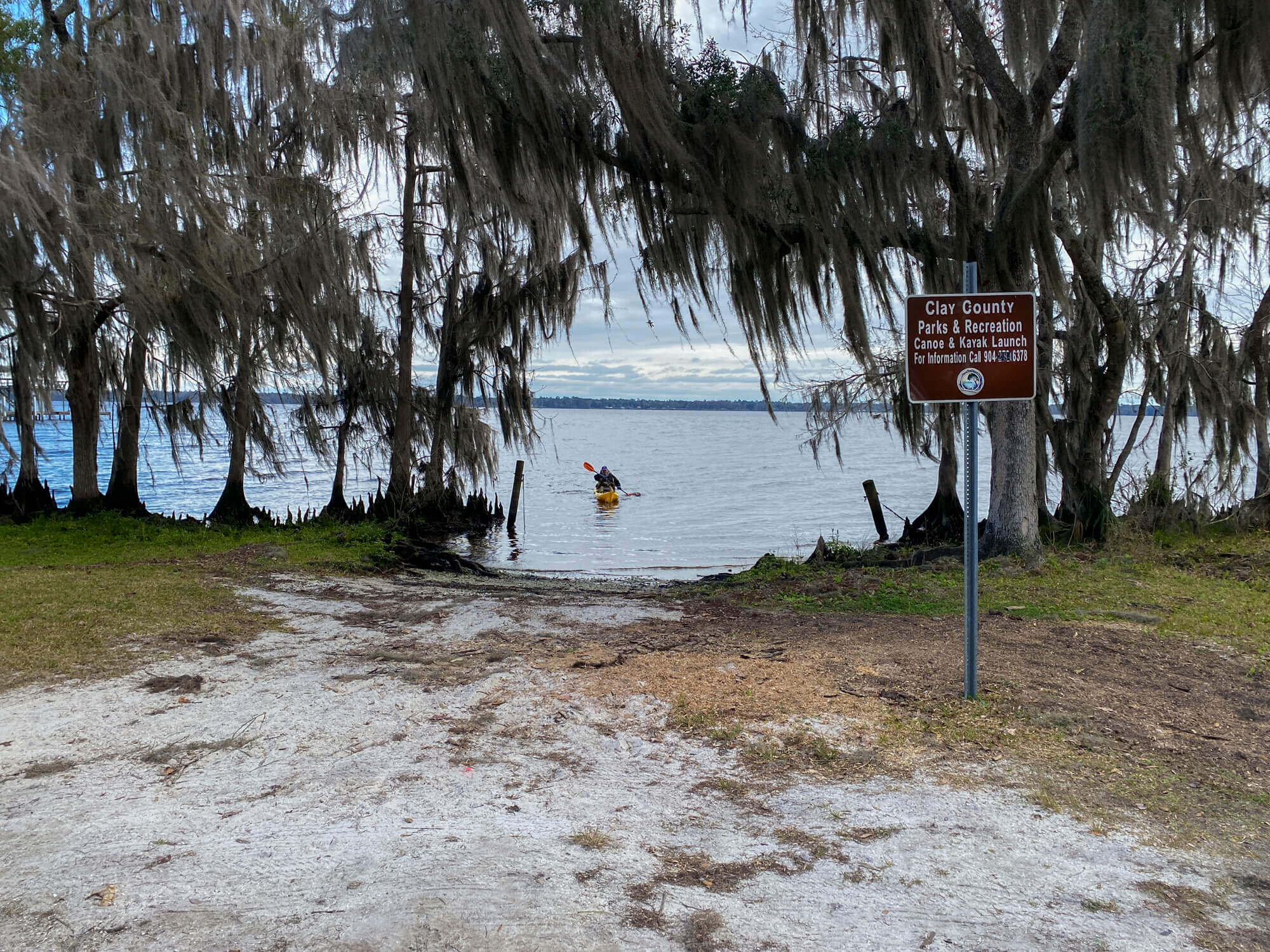

Today, this site has a county park with a small pavilion, an unimproved boat ramp, and provides limited access to the St. Johns River.

Leaving Picolata, I continued to ascend the river. I observed this day, during my progress up the river, incredible numbers of small flying insects, of the genus, termed by naturalists, Ephemera, continually emerging from the shallow water, near shore, some of them immediately taking their flight to the land, whilst myriads crept up the grass and herbage, where remaining for a short time, as they acquired sufficient strength, they took their flight also, following their kindred to the main land. This resurrection from the deep, if I may so express it, commences early in the morning, and ceases after the sun is up. At evening they are seen in clouds of innumerable millions, swarming and wantoning in the still air, gradually drawing near the river. They descend upon its surface, and there quickly end their day, after committing their eggs to the deep; which being for a little while tossed about, enveloped in a viscid scum, are hatched, and the little Larva descend into their secure and dark habitation, in the oozy bed beneath, where they remain gradually increasing in size, until the returning spring: they then change to a Nymph, when the genial heat brings them, as it were, into existence, and they again arise into the world. This fly seems to be delicious food for birds, frogs, and fish. In the morning, when they arise, and in the evening, when they return, the tumult is great indeed, and the surface of the water along shore broken into bubbles, or spirted into the air, by the contending aquatic tribes; and such is the avidity of the fish and frogs, that they spring into the air, after this delicious prey.

Early in the evening, after a pleasant day’s voyage, I made a convenient and safe harbour, in a little lagoon, under an elevated bank, on the west shore of the river; where I shall entreat the reader’s patience, whilst we behold the closing scene of the short-lived Ephemera, and communicate to each other the reflections which so singular an exhibition might rationally suggest to an inquisitive mind. Our place of observation is happily situated under the protecting shade of majestic Live Oaks, glorious Magnolias and the fragrant Orange, open to the view of the great river and still waters of the lagoon just before us.

At the cool eve’s approach, the sweet enchanting melody of the feathered songsters gradually ceases, and they betake themselves to their leafy coverts for security and repose.

Solemnly and slowly move onward, to the river’s shore, the rustling clouds of the Ephemera. How awful the procession! innumerable millions of winged beings, voluntarily verging on to destruction, to the brink of the grave, where they behold bands of their enemies with wide open jaws, ready to receive them. But as if insensible of their danger, gay and tranquil each meets his beloved mate, in the still air, inimitably bedecked in their new nuptial robes. What eye can trace them, in their varied wanton amorous chaces, bounding and fluttering on the odoriferous air? With what peace, love, and joy, do they end the last moments of their existence?

I think we may assert, without any fear of exaggeration, that there are annually of these beautiful winged beings, which rise into existence, and for a few moments take a transient view of the glory of the Creator’s works, a number greater than the whole race of mankind that have ever existed since the creation; and that, only from the shores of this river. How many then must have been produced since the creation, when we consider the number of large rivers in America, in comparison with which, this river is but a brook or rivulet.

The importance of the existence of these beautiful and delicately formed little creatures, whose frame and organization is equally wonderful, more delicate, and perhaps as complicated as those of the most perfect human being, is well worth a few moments contemplation; I mean particularly when they appear in the fly state. And it we consider the very short period of that stage of existence, which we may reasonably suppose to be the only space of their life that admits of pleasure and enjoyment, what a lesson doth it not afford us of the vanity of our own pursuits!

Their whole existence in this world is but one complete year: and at least three hundred and sixty days of that time they are in the form of an ugly grub, buried in mud, eighteen inches under water, and in this condition scarcely locomotive, as each Larva or grub has but its own narrow solitary cell, from which it never travels or moves, but in a perpendicular progression of a few inches, up and down, from the bottom to the surface of the mud, in order to intercept the passing atoms for its food, and get a momentary respiration of fresh air; and even here it must be perpetually on its guard, in order to escape the troops of fish and shrimps watching to catch it, and from whom it has no escape, but by instantly retreating back into its cell. One would be apt almost to imagine them created merely for the food of fish and other animals.

Having rested very well during the night, I was awakened in the morning early, by the cheering converse of the wild turkey-cock (Meleagris occidentalis) saluting each other, from the sun-brightened tops of the lofty Cupressus disticha and Magnolia grandiflora. They begin at early dawn, and continue till sunrise, from March to the last of April. The high forests ring with the noise, like the crowing of the domestic cock, of these social centinels, the watch-word being caught and repeated, from one to another, for hundreds of miles around; insomuch that the whole country is for an hour or more in an universal shout. A little after sunrise, their crowing gradually ceases, they quit their high lodging places, and alight on the earth, where expanding their silver bordered train, they strut and dance round about the coy female, while the deep forests seem to tremble with their shrill noise.

This morning the winds on the great river were high and against me; I was therefore obliged to keep in port a great part of the day, which I employed in little excursions round about my encampment. The Live Oaks are of an astonishing magnitude, and one tree contains a prodigious quantity of timber, yet, comparatively, they are not tall, even in these forests, where growing on strong land, in company with others of great altitude (such as Fagus sylvatica, Liquidambar, Magnolia grandiflora, and the high Palm tree) they strive while young to be upon an equality with their neighbours, and to enjoy the influence of the sun-beams, and of the pure animating air; but the others at last prevail, and their proud heads are seen at a great distance, towering far above the rest of the forest, which consists chiefly of this species of oak, Fraxinus, Ulmus, Acer rubrum, Laurus Borbonia, Quercus dentata, Ilex aquifolium, Olea Americana, Morus, Gleditsia triacanthus, and, I believe, a species of Sapindus. But the latter spreads abroad his brawny arms, to a great distance. The trunk of the Live Oak is generally from twelve to eighteen feet in girt, and rises ten or twelve feet erect from the earth, some I have seen eighteen or twenty; then divides itself into three, four, or five great limbs, which continue to grow in nearly an horizontal direction, each limb forming a gentle curve, or arch, from its base to its extremity. I have stepped above fifty paces, on a straight line, from the trunk of one of these trees, to the extremity of the limbs. It is ever green, and the wood almost incorruptible, even in the open air. It bears a prodigious quantity of fruit; the acorn is small, but sweet and agreeable to the taste when roasted, and is food for almost all animals. The Indians obtain from it a sweet oil, which they use in the cooking of hommony, rice, &c. and they also roast them in hot embers, eating them as we do chesnuts.

The wind being fair in the evening, I sat sail again, and crossing the river, made a good harbour on the east shore, where I pitched my tent for the night.

November 21, 1765

Fine morning. 67. killed A monstrous rattlesnake. PM. return’d from a jaunt in a Canoe. the. 74. we landed on ye other side of St, Johns. saw much water & large evergreen oak; ash, & A monstrous convulvolus, shrub aster, & very tall malvinda*. ye soil deep & sandy. we then came over to picolata side. ye bay seems to be A mile & half or two mile wide, some places 7 or 8. there is many coves & very rich low swamps up ye coves, produceing our common Maple, elm, & Ash with shorter seeds then ours, mirtle, red & lobloly bay, dahoon holly, some magnolia Altisimay & ye cana indica, pancratium, & water dragon. hicory is not very common here, tho there is small ones: some Cypress but few very large; cephala[nthus].

*Malvinda – Malvinda angustifolia; Moon Flower – Ipomoea alba