03 Egans Creek Park: Lord Egmont’s Plantation

Nassau County

“Mr. Egan politely rode with me, over great part of the island.”

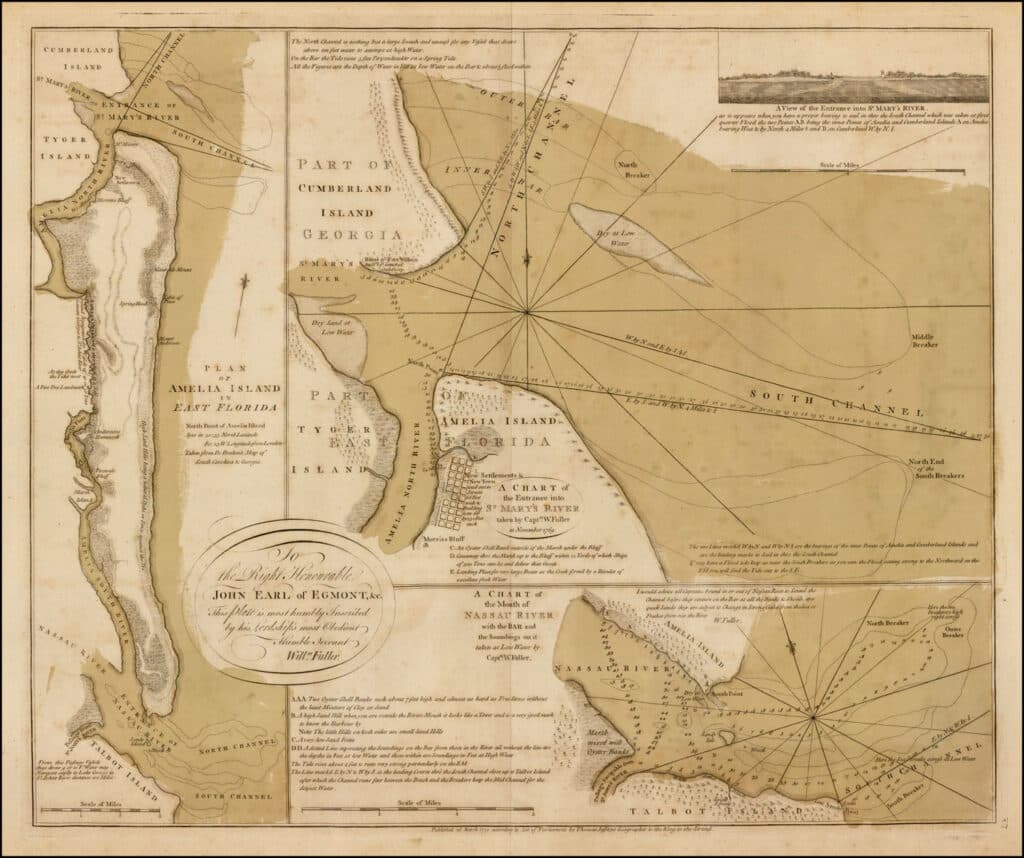

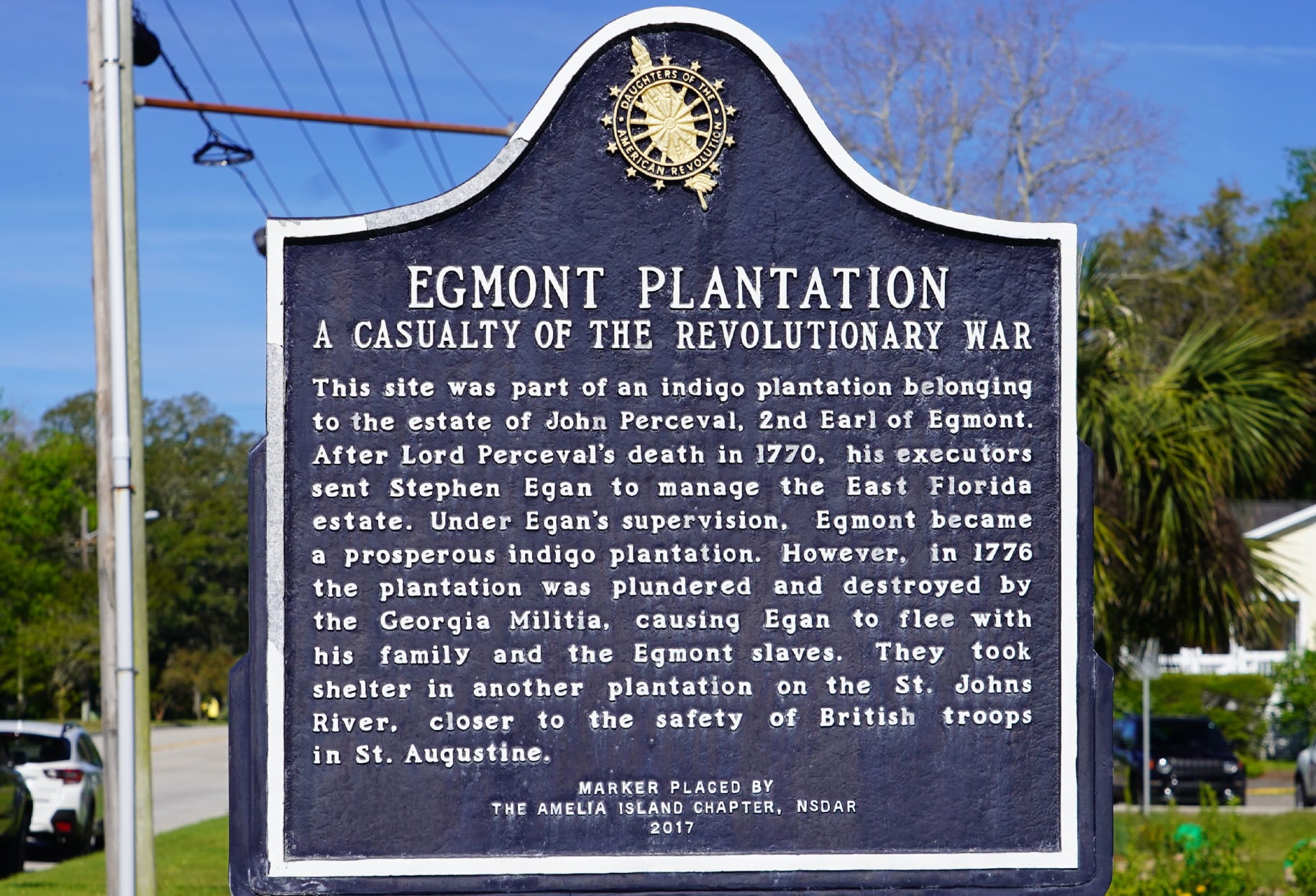

Bartram landed on the north end of Amelia Island and crossed Egan’s Creek to the headquarters of Lord Egmont’s plantation. Mr. Egan was a plantation agent or manager. The plantation contained between eight and nine thousand acres and a village called Egmont Town, which had been laid out in 1770 on the island’s northern end. Bartram remained several days on this plantation and reported that he was much impressed with the fine state of cultivation, particularly of the indigo.

According to local historians, the indigo plantation was in the northeastern sector of the present Fernandina. Bartram observed here several very large Indian mounds. Francis Harper’s commentary in the Naturalist’s Edition of Bartram‘s Travels notes that 1940 remnants of one large sand mound and three shell mounds existed.

The sand mound was on the grounds of Public School No. 1 on the north side of Atlantic Avenue near 12th Street. A large part of it had been removed in building the school or grading the grounds, so it was impossible to tell how high it had originally been. The remnant was about 10 feet above the general level. This had been described by Brinton (67), who estimated its height at 20 to 35 feet and reported that human bones and utensils had been disinterred. One of the shell mounds was about 200 yards south of the Amelia Island Lighthouse, the second about 3/8 mile east near Clark’s Creek, and the third about a mile south of the first.

Bartram left the Egmont Plantation by boat, passing through Kingsley Creek and across Nassau Sound. His party probably camped on the north end of Talbot Island, as Bartram reported a well of fresh water there; Faden’s Atlas of 1776 shows a small spring in that location. They then proceeded by way of Sawpit Creek and Sister Creek to Cow-Ford, present Jacksonville. At that time, there was a public ferry there and nearby, probably in the area of Arlington on the east side of the St. Johns opposite Jacksonville. Bartram secured a small boat and fitted it with sails for the journey up the river.

The Captain of the fort soon came up, with a slain buck on his shoulders. We hailed each other, and returned together to the fort, where we were well treated, and next morning, at my request, the Captain obligingly sat us over, landing us safely on Amelia. After walking through a spacious forest of Live Oaks and Palms, and crossing a creek, that ran through a narrow salt marsh, I and my fellow traveller arrived safe at the plantation, where the agent, Mr. Egan, received us very politely and hospitably. This gentleman is a very intelligent and able planter, having already greatly improved the estate, particularly in the cultivation of indigo. Great part of this island consists of excellent hommocky land, which is the soil this plant delights in, as well as cotton, corn, batatas, and almost every other esculent vegetable. Mr. Egan politely rode with me, over great part of the island. On

Page 66

Egmont estate, are several very large Indian tumuli, which are called Ogeeche mounts, so named from that nation of Indians, who took shelter here, after being driven from their native settlements on the main near Ogeeche river. Here they were constantly harrassed by the Carolinians and Creeks, and at length slain by their conquerors, and their bones intombed in these heaps of earth and shells. I observed here the ravages of the common grey catterpillar, so destructive to forest and fruit trees, in Pennsylvania, and through the northern states, by stripping them of their leaves, in the spring, while young and tender (Phalena periodica.)

- Egan having business of importance to transact in St. Augustine, pressed me to continue with him, a few days, when he would accompany me to that place, and if I chose, I should have a passage, as far as the Cow-ford, on St. Johns, where he would procure me a boat to prosecute my voyage.

IT may be a subject worthy of some inquiry, why those fine islands, on the coast of Georgia, are so thinly inhabited; though perhaps Amelia may in some degree plead an exemption, as it is a very fertile island, on the north border of East Florida, and at the Capes of St. Mary, the finest harbour in this new colony. If I should give my opinion, the following seem to be the most probable reasons: the greatest part of these are as yet the property of a few wealthy planters, who having their residence on the continent, where lands on the large rivers, as Savanna, Ogeeche, Altamaha, St. Ille and others, are of a nature and quality adapted to the growth of rice, which the planters chiefly rely upon, for obtaining ready cash, and purchasing family articles; they settle a few poor families on their insular

Page 67

estates, who rear stocks of horned cattle, horses, swine and poultry, and protect the game for their proprietors. The inhabitants of these islands also lay open to the invasion and ravages of pirates, and in case of a war, to incursions from their enemies armed vessels, in which case they must either remove with their families and effects to the main, or be stripped of all their movables, and their houses laid in ruins.

THE soil of these islands appears to be particularly favourable to the culture of indigo and cotton, and there are on them some few large plantations for the cultivation and manufacture of those valuable articles. The cotton is planted only by the poorer class of people, just enough for their family consumption: they plant two species of it, the annual and West-Indian; the former is low, and planted every year; the balls of this are very large, and the phlox long, strong, and perfectly white; the West-Indian is a tall perennial plant, the stalk somewhat shrubby, several of which rise up from the root for several years successively, the stems of the former year being killed by the winter frosts. The balls of this latter species are not quite so large as those of the herbacious cotton; but the phlox, or wool, is long, extremely fine, silky, and white. A plantation of this kind will last several years, with moderate labour and care, whereas the annual sort is planted every year.

THE coasts, sounds, and inlets, environing these islands, abound with a variety of excellent fish, particularly Rock, Bass, Drum, Mullet, Sheeps-head Whiting, Grooper, Flounder, Sea-Trout, [this last seems to be a species of Cod] Skate, Skip-jack, Stingray, the Shark, and great Black Stingray,

Page 68

are insatiable cannibals, and very troublesome to the fishermen. The bays and lagoons are stored with oysters and varieties of other shell-fish, crabs, shrimp, &c. The clams, in particular, are large, their meat white, tender, and delicate.

THERE is a large space betwixt this chain of seacoast-islands and the main land, perhaps generally near three leagues in breadth; but all this space is not covered with water: I estimate nearly two thirds of it to consist of low salt plains, which produce Barilla, Sedge, Rushes, &c. and which border on the main land, and the western coasts of the islands. The east side of these islands are, for the most part, clean, hard, sandy beaches, exposed to the wash of the ocean. Between these islands are the mouths or entrances of some rivers, which run down from the continent, winding about through these low salt marshes, and delivering their waters into the sounds, which are very extensive capacious harbours, from three to five and six to eight miles over, and communicate with each other by parallel salt rivers, or passes, that flow into the sound: they afford an extensive and secure inland navigation for most craft, such as large schooners, sloops, pettiaugers, boats, and canoes; and this inland communication of waters extends along the sea coast with but few and short interruptions, from the bay of Chesapeak, in Virginia, to the Missisippi, and how much farther I know not, perhaps as far as Vera Cruz. Whether this chain of sea-coast-islands is a step, or advance, which this part of our continent is now making on the Atlantic ocean, we must leave to future ages to determine. But it seems evident, even to demonstration, that those salt marshes adjoining the coast of the main, and the reedy and grassy islands and marshes in the rivers, which are now overflowed at

Page 69

every side, were formerly high swamps of firm land, affording forests of Cypress, Tupilo, Magnolia grandiflora, Oak, Ash, Sweet Bay, and other timber trees, the same as are now growing on the river swamps, whose surface is two feet or more above the spring tides that flow at this day; and it is plainly to be seen, by every planter along the coast of Carolina, Georgia, and Florida, to the Missisippi, when they bank in these grassy tide marshes for cultivation, that they cannot sink their drains above three or four feet below the surface, before they come to strata of Cypress stumps and other trees, as close together as they now grow in the swamps.

However I chose to continue my journey to east Florida, in expectation of a more favourable turn of affairs and having some papers in my baggage that I did not like to lose, so I got put on shore at Fort William on South Point of Cumberland, where lived the pilot of St. Mary’s River who sent me over on Amelia Island, where I was very hospitably entertained by Mr. Egan, Agent for Lord Egmont, here are great plantations for the culture of Indigo. Mr. Egan showed me samples of his Indigo which was the best I had yet seen. I stayed two or three days with this gentleman on his promising me a passage with him to St. John’s.

Observed some large Indian Mounts and the vestiges of great towns and square of the ancient Indian Natives, observed a very beautiful species Lycium with a blue flower and a coral red fruit, a most elegant shrub, it’s ever gay with flowers, ripe and green fruit, and a beautiful Thymallus, with curious leaves being painted with a bright vermilion color near the pedicle. Went with Mr. Egan in his boat rowed by negroes, this night encamped on a shell bluff within a few miles of the River St. John’s, got some excellent oysters which we roasted for supper, rested very well under a vast spreading Live Oak, making a fire to keep off the mosquitoes.

Footnotes

N.B. Page numbers for all Bartram quotations will be given in the following way: The first page number cited will be the page on which the passage appears in the first (Philadelphia 1791) edition of the book; the second page number will be the page on which the passage appears in Francis Harper’s Naturalist’s Edition. For convenience in checking the original source, Harper’s edition provides both systems of pagination. When third or fourth numbers appear, they refer to Harper’s commentary, also in the Naturalist’s Edition.

66. For this account of Bartram’s trip through Florida in 1774, the Bartram Trail Conference is indebted to Dorothy Driggers, op. cit.

65. Bartram’s Travels, p. 65, Harper, p. 42.

67. Daniel G. Brinton, Notes on the Florida Peninsula; Its Literary History, Indian Tribes, and Antiquities, Philadelphia, 1859.

Bartram’s Report to Fothergill online: Report to Fothergill (usf.edu)