Photo credits: “A View of the Ancient Chunky Yard” (Fig 2) taken from “Observations of the Creek and Cherokee Indians.” William Bartram, 1789

Billy Bartram is best known as an explorer, botanist, artist and writer. But readers often don’t realize that he described and sketched many encounters with Native Americans. His observations, views and writings on these people were influential in his own time, lending support to the infamous “civilization policy” for the budding American united colonization and new government. Today, these descriptions serve as a valuable resource to contemporary archaeologists, anthropologists and cultural history aficionados.

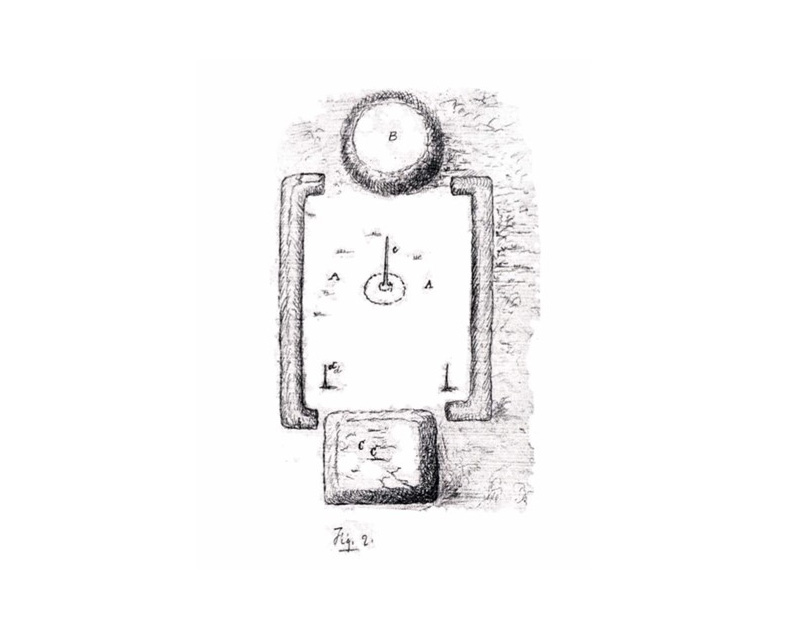

A great example of this is Billy’s sketch “A View of the Ancient Chunky Yard” taken from “Observations of the Creek and Cherokee Indians” which he had published in 1789, two years before “Travels” was officially published in 1791.

Creek Indian athletic and ceremonial fields, and associated structures, were the heart of the village, a meeting place for leaders and shamans, as well as greeting and entertaining visitors. Bartram likely encountered these town centers in larger villages he visited in the East Florida Territory. One such settlement, was Cuscowilla, a large village located adjacent to the Great Alachua Savannah, now Payne’s Prairie Preserve State Park, near modern-day Gainesville.

Bartram’s sketch details the raised earthen banks enclosing the yard, the result of repeated sweeping. The area was used for “Chunky,” a favorite Creek hoop and stick game. It was played between two opponents, one rolling a stone disc across the ground and the other throwing a spear in an attempt to place the spear as close to the stopped stone as possible. The game would often continue until both players were exhausted. The intention of the games seemed to be the gathering of large groups of neighboring villages and even visitors. Gambling was frequently connected to the game, with some players wagering everything they owned on the outcome of the game. Losers were even known to commit suicide.

Stone images were by Peach State Archaeological Society, 2024

The stones were considered valuable objects and as community, not individual property and they were not allowed to be used as burial objects.

Bartram’s sketch depicts and suggests a single-pole ball game on the tall post in the center (A). Also shown in the sketch corners are “slave posts” (D) where war captives were ritually tortured and executed. The diagram shows the location (B) of an elevated rotunda or “circular eminence” where village leaders or council would view the games or ceremonies. The square council house (C) likely contained four smaller cabins and beds structures for village leaders and visitors. As with many of Bartram’s sketches, drawn from memory and copious notes, the Chunky Yard (Fig 2) was completed much later following the actual encounter in the field. Often the scale of the drawings could be skewed. In reality, both the council house and elevated rotunda were further back, away from the Chunky yard.

Preceded by the regional ancient Timucuan, these Creek games and ceremonies occurred throughout much of North America particularly in the Southeast. It’s highly possible that the stones were traded and imported from other regions and tribes. They also paralleled similar activities, games and rituals with native peoples to the south, such as the Aztec, Maya and Inca in Mesoamerica.

Mike Adams is an anthropologist, ecologist, educator, researcher and author. He has lived in worked along the St. Johns River since 1980. He is a member of the Bartram Trail Society of Florida, headquartered in Palatka.